Georgia’s “Rose Revolution”, like Ukraine’s “Orange Revolution”, is precisely the kind of popular uprising that the Russian elite fears most deeply. Any Western support for the Georgian cause will only increase Russian paranoia. The big question asked these days is whether the Kremlin bosses would have dared attacking Georgia, if it was already part of NATO?

But Moscow’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia risks starting a “domino effect,” by re-awakening separatist sentiments in Chechnya and other parts of the turbulent North Caucasus where Russia has been fighting to contain rebellions. Some Chechens have already expressed bitterness, of double standard, that Russia was backing separatists in South Ossetia and Abkhazia, yet fought two devastating wars to crush Chechnya’s short-lived independence. In nearby Ingushetia and Dagestan, disparate groups of Islamist militants regularly mount bomb attacks and ambushes indicating their demand to establish Islamic rule there.

So what is Moscow trying to signal by it’s new aggressive attitude? Less than four months after taking office, Russia’s youthful figurehead Dmitrij Anatol′evič Medvedev has invaded a European country, for the first time since Prague forty years ago and cast a chill over relations with the West. On the face of it, the Kremlin may be trying to play again in the big league game, but can it afford to do so in 2008?

Russia may sound belligerent, but its leaders know very well, that they command only a fraction of the power of the old Soviet Union. The Kremlin’s total defense budget is about $70 billion. America, by contrast, spends ten times more – almost half of all the military expenditure in the entire world. Moreover, America’s economy is almost 14 times bigger than Russia’s, even if Russia decides to spend seven per cent of its entire national output on defense it will reach a military budget that is only 11 per cent of America’s today. But that’s not all. The effects of Russia’s first foreign war as a capitalist country already rippled through the Moscow stock markets, which dipped to their lowest level since 2006. If Washington decides to oust Russia from G8, the effect on Moscow’s economy could be disastrous.

But on the other hand, Russia is far from going broke, as it did in the financial collapse of 1998. Any Western effort to punish Russia economically will surely be softened by the surging demand for Russian oil and natural gas in Western Europe and Asia. Western Europe is totally dependent on Russian gas to keep it warm over the winter. Moreover, while the stock market stumbled, the country’s trade surplus and the profits of its leading energy companies remained as robust as ever. Russia holds about $600 billion in foreign exchange and gold reserves. But whether all this wealth can render sufficient wielding power for new military adventures, remains extremely questionable.

At present, Russian analysts remain confident in their leadership’s attitude. In their view, the United States and the nations of Europe may not like what Russia is doing, but officials in Moscow believe those countries lack the leverage, strength or unity to intervene. Some are saying it clearly – that the west no longer exists as a unified force.

Indeed, there are those in Moscow, who strongly believe that the time has come to flex muscles against Washington’s “missile strategy” in Eastern Europe, which the Kremlin still regards part of it’s sphere of strategic interest.

They regard the U.S. floundering economically and bogged down in two costly wars. Russian officials were confident that it could not and would not come rushing to Georgia’s defense with a military intervention. Moreover, Europe, meanwhile, depends upon Russian oil and gas exports, and was leery of a conflict with Moscow that could further raise fuel prices. They were more or less right in their assessment. In response to Russia’s aggression, NATO, and the U.S. remained passive during the war, and limited their response humanitarian aid and to verbally scolding Moscow’s action. As a sign of support, the U.S. Navy guided-missile destroyer McFaul arrived at the Georgian port of Batumi unloading baby food and bottled water.

Another issue, after the lightning invasion of Georgia, is raising concern that the next flash point may be Ukraine’s Black Sea peninsula, the Crimea. This area once part of Russia still provides a key warm-water port for the Russian Navy. With regional tensions inflamed over Georgia, other neo-Cold War fights are brewing. Many Russians are keeping a close eye on Ukraine, whose loss remains an existential challenge to a Russian culture that traces its empire to the banks of the Dnieper River. Moscow has long resisted the notion that Ukraine is an independent nation.

For the Russians, the Crimea is an issue of strategic importance, even more than pride or nationalism. Russia’s Black Sea naval fleet is based at Sevastopol, a city located at the tip of the Crimea peninsula. Russia holds a lease to the naval base until 2017, though in recent years Ukrainian politicians have made clear that they are eager for the Russian Navy to pull out. But the Ukraine is no military pushover like little Georgia. If Moscow decides to go to war with Kiev, it would face an adversary, both well armed and motivated to give the invaders a good beating, which they can hardly afford. Moerover, geographically, bordering with post allied countries, now NATO members – Romania, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland, Ukraine may get much more active support than Georgia, located far away in the Caucasus. But an all-out military conflict involving NATO or the U.S., seems illogical, even under the worst circumstances.

Defense Secretary Robert Gates ruled out using U.S. military force in Georgia but he said the Pentagon would review all aspects of its relations with Russia’s military. Gates, the most experienced Russia expert in the top ranks of the Bush administration, said Moscow’s actions had “profound implications for our security relationship going forward, both bilaterally and with NATO”. Gates added that “If Russia does not step back from its aggressive posture and actions in Georgia, the U.S.-Russian relationship could be adversely affected for years to come”. As a former CIA director and Soviet expert at the intelligence agency, Gates meant what he told reporters at the Pentagon. “The United States spent 45 years working very hard to avoid a military confrontation with Russia. I see no reason to change that approach today, Washington does not wish to enter into a new “Cold War” era.

But there is another aspect of the present situation, which is not fully comprehended in the West. After years of total neglect and financial ruin, the Russian armed forces are still fighting to reform. Russia’s armed forces have yet to complete their transition from an expensive Cold War model designed for a global conflict to a leaner, meaner modern war machine. In fact, a Washington Think Tank believes there was hardly any hope for Russia to create a modern and effective army before 2020.

Director of National Intelligence John Michael McConnell defined Russia’s military threat, taking account of the increase in investments in defense and the reform of the armed forces on the part of the Russian government. In a document presented to the US Senate he argued that “Russia’s military officials have set to the restoration of the armed forces after a long and deep crisis, which started even before the collapse of the Soviet Union. But sofar, apart from massive propaganda, little has actually been achieved to restore Russia’s armed forces into a modern fighting force, capable in playing in the western court. ”

Efforts to reform the military are hobbled by corruption. Official Russian government sources admitted the government prosecuted 196 senior officers for corruption last year. Newly elected president Dmitry Medvedev is trying to get an anti-corruption law passed but, so deeply entrenched in Russian tradition, this new law meets heavy resistance, since so many legislators get some of their income from corrupt practices.

Efforts to reform the military are hobbled by corruption. Official Russian government sources admitted the government prosecuted 196 senior officers for corruption last year. Newly elected president Dmitry Medvedev is trying to get an anti-corruption law passed but, so deeply entrenched in Russian tradition, this new law meets heavy resistance, since so many legislators get some of their income from corrupt practices.

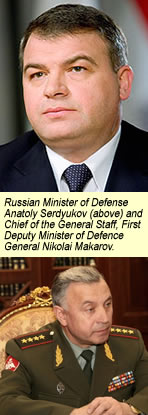

Earlier this year Russia’s new president started to act decisively. Medvedev dismissed Russia’s top military officer in an apparent effort to assert Kremlin control over the armed forces and smooth the path for reforms. The powerful general, Yuri Baluyevsky, First Deputy Minister of Defense and chief of staff of the armed forces since July 2004, was replaced by General Nikolai Makarov, an ally of the “civilian” Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov. Baluyevsky became known as an outspoken officer when, last January he warned that “Moscow could use nuclear weapons in preventive strikes in case of a major threat”. Russian sources explained the general “had to be eliminated”, since General Baluyevsky was in an open fight with the defense minister, resisting his reforms. General Makarov’s new job is “to perform one of the key missions Serdyukov was given – to put some order into the Defense Ministry and its procurement program,” a far from easy job in the highly traditional Russian hierarchy.

In fact, professional Russian officers are placing great hopes on General Makarov – a reformer, and perhaps most importantly, fully loyal to his new boss, the defense minister, Makarov has all the right credentials to become head of Europe’s largest military. A career military officer who has risen through the ranks, The general places greater emphasis on training and educating troops under his commands, an issue that the old Soviet army and the Russian army traditionally have always ignored. In preferring the traditional command chain, the ‘old school’ assured the top command full control, but left the combat command level – little or no scope for initiative. In contrast, Makarov emphasizes the formation on flexible, well trained, armed forces. This approach will be vital for the Russian ambition to establish a flexible armed forces that, like the 21st century U.S. armed forces. Whether this will actually work within the rigid former Soviet system remains to be seen, however.

While the Russian army seems far better than it was in the 1990s they are still in a crisis. In spite of some dramatic developments, which were highly publicized, Russia’s military-industrial complex was still unable to produce sophisticated, advanced equipment that could match the Western superior equipment in this field. Countries opting for Russian equipment for its competitive cost sooner or later upgrade their hardware with costly modernizations, integrating western systems where possible. Moreover a major stumbling block is manpower. Over 90 per cent of young Russians manage to dodge the draft, often through bribery, leaving only the poorest and unhealthiest to fill the ranks. According to Russia’s air force commander, 55 per cent of his draftees suffered from either drug or alcohol problems, malnutrition or “mental instability”, while many could not read or write. Across the board, there is a very small amount of skilled cadre in the military.

Meanwhile, there is still deep discontent growing among the highest orders of Russia’s Ministry of Defense. Senior military officers are dissatisfied with the performance of Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, whom they regard as an alien outsider. Several military leaders are considering resignation, and others have already turned in their document, seeking jobs in a more lucrative civilian sector. General Makarov will have to work very hard to clean the stables and get his army on a new heading. Indeed, Russia is going to have to come to terms with the reality it can either integrate with the world or it can be a self-isolated bully. But it can’t be both.