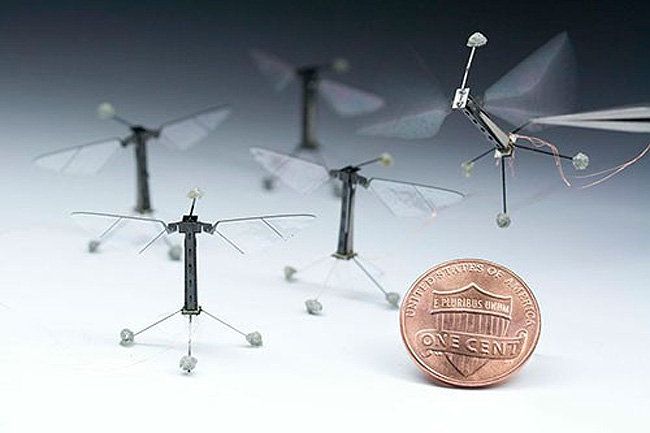

A team of researchers from the Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) are developing an insect sized robot that made its first flight last summer. Half the size of a paperclip, weighing less than a tenth of a gram, RoboBee inspired by the biology of a fly and conceived through manufacturing breakthrough and miniaturization.

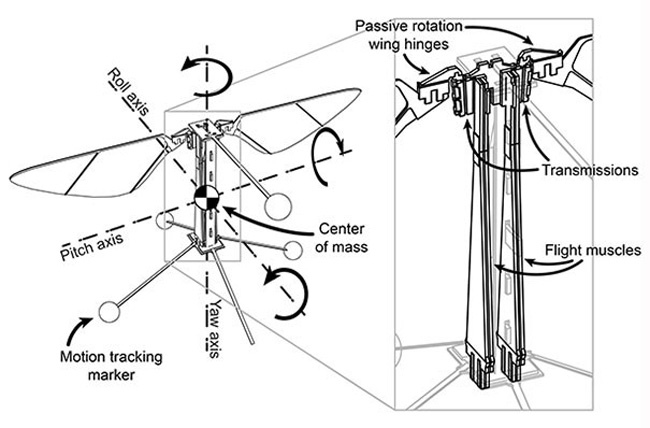

The unique submillimeter-scale anatomy of RoboBee uses two wafer-thin wings that flap almost invisibly, 120 times per second. At tiny scales, small changes in airflow can have an outsized effect on flight dynamics, and the control system has to react that much faster to remain stable. For the wing ‘muscles’ the tiny robot employs piezoelectric actuators – strips of ceramic that expand and contract when an electric field is applied. Thin hinges of plastic embedded within the carbon fiber body frame serve as joints, and a delicately balanced control system commands the rotational motions, differentially moving the flapping wings to generate directional motion.

The first flights that took place in the summer of 2012 employed a tethered version feeding power and processing from external devices. The next steps in the program will involve integrating the parallel work of different research teams who are working on the brain, the colony coordination behavior, the power source, etc., leading to the evolution of fully autonomous, wireless robotic insects. High energy-density fuel cells must be developed before the RoboBees will be able to fly with more independence.

Applications of the RoboBee type ‘creatures’ could include distributed environmental monitoring, search-and-rescue operations, or assistance with crop pollination, but the materials, fabrication techniques, and components that emerge along the way might prove to be even more significant. The US Air Force is also working on similar technologies, under the Air Force Research Lab Micro-Aviary program. The US Army is also working on micro-bots, through thethe Army Research Laboratory’s (ARL) Micro Autonomous Systems and Technology (MAST) Collaborative Technology Alliance.

According to Robert J. Wood, principal investigator of the National Science Foundation-supported RoboBee project, the lab’s recent breakthroughs in manufacturing, materials, and design have paved the way for the new achievement of RoboBee. “Now that we’ve got this unique platform, there are dozens of tests that we’re starting to do, including more aggressive control maneuvers and landing,” says Wood. The robotic insects also take advantage of the breakthrough pop-up manufacturing technique developed by Wood’s team in 2011.

Through the Pop-Up Manufacturing process (video) sheets of various laser-cut materials are layered and sandwiched together into a thin, flat plate that folds up like a child’s pop-up book into the complete electromechanical structure. The process enabled the team to accelerate prototype development, going through 20 prototypes in a six months period. The pop-up manufacturing process could enable a new class of complex medical devices.

Harvard’s Office of Technology Development, in collaboration with Harvard SEAS and the Wyss Institute, is already in the process of commercializing some of the underlying technologies. The program was supported by the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard.