North Korea conducted yesterday (July 28) a second flight test of an Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). The missile was launched at 23:41 local time (15:41 GMT) from an arms plant in Jagang province in the north of the country, the Pentagon said.

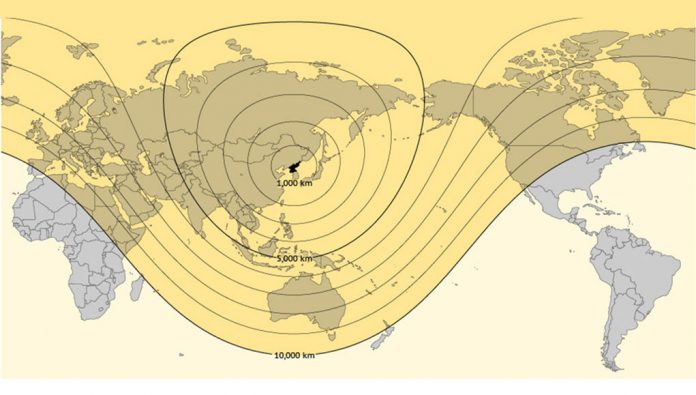

Pyongyang officially confirmed the event, adding the missile being tested was Hwasong-14, claiming now that it has the entire continental US within range. The missile flew 998 kilometer for about 47 minutes reaching a maximum altitude of 3,724.9 km. In terms of maximum range trajectory it could fly as far as 10,000 km.

It is unusual for North Korea to launch a missile at night – the significance is as yet unclear. It could have chosen to avoid surveillance by South Korean and the U.S. intelligence assets or for other reasons.

No missiles had been fired from Jagang province before, indicating a previously-unknown launch site is operational.

Using this new launch site North Korea may push to set up an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launch base and related infrastructures in the northern province of Jagang, where many armament industry facilities are located.

According to Michael Ellman, of 38north.org, on July 4, 2017, North Korea conducted its first test of a two-stage Hwasong-14 ballistic missile, which reached an apogee of about 2,800 km. If flown on a standard trajectory, this means the Hwasong-14 would have a maximum range in excess of 7,500 km—intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) range—and may be able to reach the US west coast if armed with a warhead weighing 650 kg or less. However, the Hwasong-14 tested on July 4 was not optimally designed to achieve maximum range. Instead, it appears to have been a prototype designed to maximize the probability of a successful maiden flight by relying on flight-proven stages.

The first Hwasong-14 tested on July 4 employed a first stage based on the Hwasong-12, but with a slightly larger diameter to carry more propellant. The second stage was similar to the third stage of North Korea’s satellite launch vehicle, the Unha. For an ICBM, however, the second stage was under-sized and underpowered, making it ill-suited for use on a ballistic missile. One would assume that future tests of the Hwasong-14 would require North Korea to reconfigure the second stage for a better performance.

On July 28, North Korea launched a ballistic missile that reportedly flew for 45 minutes, reaching a peak altitude of 3,000 km, and a slightly longer range than the previous test. While the type of missile tested is yet unconfirmed, these data, if accurate, are fully consistent with a Hwasong-14 tested with a larger second stage that is powered by a high-thrust engine. If flown on a flatter trajectory, this missile could reach as far as 9,000 to 10,000 km. More information, including videos and photographs, will help identify the new second stage engine and pinpoint its performance capacity.

However, if the above assessment is correct, North Korea seems to have made a logical step forward, as it tries to perfect the technologies to build and field an operationally-viable ICBM that can threaten the mainland United States. More tests are needed to assess and validate the reliability of the Hwasong-14, so North Korea is sure to follow this launch with much more.

Following the announcement, South Korean President Moon Jae-in ordered discussions to be held with the United States on deploying additional anti-missile defense units. Moon also called for stronger sanctions against the North.

Two Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) launch systems are currently deployed in South Korea, along with the system’s AN/TPY-2 radar. Deployment of four additional was planned but delayed over concerns about their environmental impact. While Hwasong-14 does not put South Korea at risk, there are plenty other ballistic missiles within range. However, the THAAD positioned in South Korea is designed to intercept missiles as they descend to their target.

A Boost Phase Interception system is required to eliminate the North Korean ICBM missiles threat. Such a system could deploy air, ground or sea based missile interceptors relying on airborne sensors for early warning. The US Missile Defense Agency have tested such systems on MQ-9 Reaper drones and plans to deploy such sensors in the coming years. South Korea provides an operational base for such systems, which could shield the entire hemisphere from the rapidly growing missile threat from North Korea.