Racing to the Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), Pyongyang’s long-range missile activity means bad news for Japan and South Korea, since the medium and intermediate range missiles developed by the rough nation could target even well-defended targets in the Western Pacific, including Japan, South Korea and US bases in the region. A trilateral missile defense drill held this week in the Sea of Japan demonstrated the intelligence sharing, early warning, and missile engagement capabilities that the USA, Japan, and South Korea could share on mutual defense, should a North Korean missile attack happens. Such an attack could occur by a deliberate act of either side or due to an ‘accidental strike’ caused by misinterpretation of and warnings.

Both regional powers do not have a bilateral defense cooperation, but they share such agreements with the USA, to enable intelligence-sharing and ballistic missile defense, as North Korea continually threatens both. The recent exercise was the sixth trilateral drill of this kind, followed North Korea’s first-ever ballistic missile flights over Japan, with the Hwasong 12 intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) tests in August and September. North Korean missiles are launched at high loft trajectories designed to test their propulsion systems through their full burn time, as they are traveling high into space, but only few hundred kilometers toward their designated targets at the Sea of Japan. On their descent, these missiles reach very high velocity, almost double that of short-range missiles. Therefore, such attack profiles could also be used against real targets in South Korea, the US bases in Okinawa or Japan, challenging existing defense systems with much more potent, and faster threats they were not designed to kill.

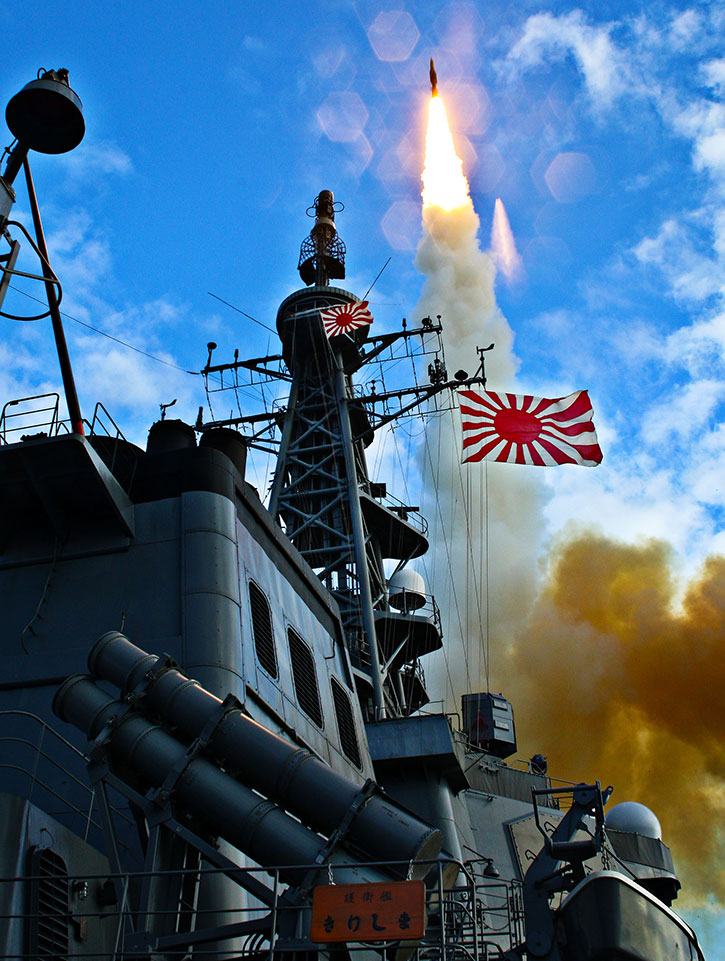

These recent threats unveiled a gap in allied ballistic missile intercept capabilities in the region, currently relying on ship-based SM-3 interceptors, land-based THAAD, and Patriot air and missile defense systems. Amid North Korea’s repeated missile launches, Aegis vessels are continuously on alert in the Sea of Japan, and Japanese Patriot missile batteries are maintained on high alert to intercept missiles that could have avoided the SM-3.

PAC-3 is not likely to be the answer to the increased ballistic missile threat from North Korea. Tokyo has earmarked ¥20.5 billion (US$180 million) in its defense budget to improve the system with Patriot Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE) program. As the improved missile reaches longer range and higher altitude, it can better intercept ballistic missiles, as well as cruise missiles and airplanes.

Another improvement will be the planned deployment of SM-3 Block IIA interceptors on American and Japanese missile defense vessels. Japan helped to develop this variant and will spend ¥47.2 billion (US$418 million) next year on the initial fielding of these interceptors on board its AEGIS destroyers. A future deployment of AEGIS aShore in Japan could better cope with those threats.

The Japanese Cabinet of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is soon expected to approve a plan to deploy two ‘AEGIS Ashore’ missile defense sites on Japanese land comprised of the SM-3 Block IIA interceptors. Each site could cost about ¥80 billion (US$700) Such deployment could be completed by 2023. Two sites could cover almost the entire area of Japan and add possibly mid-course intercept capability to ballistic missiles overflying the country on their way to US islands in the Pacific. The introduction of Aegis Ashore and Patriot MSE in Japan will complete a renovation of the Island state’s multi-tier missile defense system that now faces new threats.

Although the new missile failed its second test in June, the US Missile Defense Agency plans to deploy the SM-3 Block IIA missile with the second European based AEGIS Ashore site in Poland next year (2018). The first base was activated in Romania in 2016.

Unlike Japan’s reliance on US-developed missile defense capabilities, Seoul prefers to rely on indigenous assets. In recent years South Korea has been fielding a multi-tier missile defense system known as KAMD. The system is based on locally developed weapon systems and utilizes some technologies acquired abroad. The primary sensors for KMAD are EL/M2070 Green Pine radars obtained from Israel (one radar has been fielded, a second was ordered this year). The lower tier of KAMD is KM-SAM Cheongung medium-range surface-to-air missile system and its PIP missile interceptor, developed in cooperation with the Russian air defense expert Almaz Antey. By spring of 2017, the PIP missile performed a successful final developmental test series, that cleared the new missile to proceed to full-scale production. Full deployment is expected around 2019.

As the new KM-SAM enters service, the Korean Patriot will maintain the mid-tier, with PAC-2 units upgraded to Patriot MSE class. But, even with MSE, the Korean missile defense still requires an upper-tier, which is currently provided by the THAAD missile defense system deployed in South Korea by the US Army in April 2017. By 2022 Seoul plans to introduce a new interceptor known as L-SAM or Cheolmae-4. Four are scheduled for deployment throughout South Korea by 2025. But these are plans and with the growing activity in North Korea, missile defense is an immediate challenge.

Currently, the US Army has four THAAD fire units positioned in Seongju, 135 km south of Seoul, with an AN/TPY-2 radar, following increased missile activity in North Korea. While the THAAD interceptor provides an excellent answer to short-range missile threats fired against US bases in the country or South Korean targets, its interceptors are less than optimal intercepting medium or intermediate-range ballistic missiles, on their ascent and intermediate trajectory. Enhancements of the THAAD are planned to introduce an “extended range” version of the missile (THAAD-ER), which will increase the weapon’s intercept range to more than 150 kilometers. THAAD’s AN/TPY-2 radar system already covers the long range that those THAAD-ER missiles will provide.

In fact, this radar already causes much concern across the Yellow Sea, in Beijing. For months, Seoul and Beijing appeared to have been deadlocked over their dispute over THAAD. China has insisted that South Korea remove the system, saying it could not tolerate its powerful radar on its doorstep. By the end of October Seoul and Beijing reached a compromise to bring bilateral relations back to normal.

Russia and China have common strategic interests in the region but do not have a military alliance. Therefore, the two sides do not share sensitive intelligence, threat intelligence or real-time warning and tracking from sensors that can reduce response time in critical situations. Thus, a form of shared C2 is the least they can do to deal with missile threats in emergencies.

Both Russia and China also have missile defense capabilities in the Far East. As the manufacturer of the short and medium range ballistic missiles now proliferating worldwide, Russia has also deployed the antidotes – two generations of operational ballistic missile interceptors – the S-300 and S-400 systems. The two types differ in their capability to deal targets at higher reentry speed. S-300 can intercept ballistic missiles with a range of 2,500 km, at reentry velocity of 4.5 km/sec while the S-400 can deal with missiles with a range of 3,500 km, which develop reentry speed of five kilometers per second. According to analysts. When used in point defense role, these interceptors can successfully engage a single, non-maneuverable warhead of a missile fired from 5,500 km (thus classified as an intercontinental ballistic missile – ICBM) At the same time.

China also deploys land and sea-based derivatives of the HQ-9 – HQ-19 and HQ-29 are variants armed with anti-missile warheads, the HQ-19 uses a dual-purpose exoatmospheric kinetic kill vehicle, while HQ-29 is built for endoatmospheric hit-to-kill engagement. HQ-26 is the naval variant of the HQ-19 missile.

With higher risk of a missile war in the Korean Peninsula and the Western Pacific, Russia and China are also at risk, primarily from accidental strikes. To test their defenses, the two countries are holding a week-long anti-ballistic missile defense simulation in Beijing this week. The exercise, dubbed ‘Airspace Security 2017’ is the second missile defense exercise held by the two countries, the previous event was held in 2016 in Moscow. The drill aims to examine command and control (C2) aspects in joint response to ‘accidental and inflammatory strikes of ballistic missiles’, the Russian MOD announcement said. Both sides insist the drill does not target a third country (such as North Korea).