Start < Page 1 of 8 >

In July 2007, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates asked Congress for approval to transfer nearly $1.2 billion to the Pentagon’s Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) program to procure an additional 2,650 vehicles. SInce then, the program further evolved and is now about to include some over 15,000 vehicles. With an estimated budget of over $25 billion, MRAP is positioned to become the Defense Department’s third-largest acquisition program, behind only the missile defense and Joint Strike Fighter programs. Is it the right choice? When will the money come from? What will the military do with these vehicles as the current conflict wind down? This article does not have the answers, but reading through the lines, one realizes there are many open questions, and only few answers.

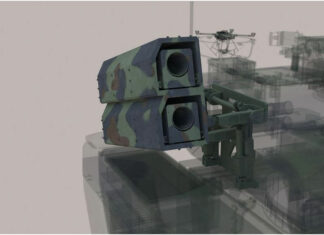

Vehicle Armoring

There are basic elements linking key elements in planning war machines – mobility, firepower and protection. One does not go without the other. Through trial and error, military designers learned to balance between the three, creating highly effective, efficient machines that won the trust of the soldiers while spreading fear and terror among their opponents. However, sensitive and highly dangerous vulnerability gaps emerge wherever this balance is tipped.

There are basic elements linking key elements in planning war machines – mobility, firepower and protection. One does not go without the other. Through trial and error, military designers learned to balance between the three, creating highly effective, efficient machines that won the trust of the soldiers while spreading fear and terror among their opponents. However, sensitive and highly dangerous vulnerability gaps emerge wherever this balance is tipped.

This, in a nutshell, is the motivation behind armoring a soldier or a vehicle – applying sufficient armor for optimal protection, without jeopardizing mobility, situational awareness and firepower. As armor is always heavy, there will always be demand for better protection ‘somewhere’, but maximizing protection under any circumstances is the wrong approach- it has its price.

Asymmetric warfare that has emerged since the second half of the 20th century, challenged the military to adapt doctrines and means to fight a protracted war. In past conflicts, there were clear definitions between ‘front line’ elements, which were normally better protected, particularly in the frontal area facing the enemy, while rear echelons, which were not armored at all, since they rarely had to engage in severe fighting and then, using only weapons for self defense. Modern asymmetrical warfare has emphazised the fluid battlespace, and since insurgents might appear everywhere, this type of warfare requires a different approach to enhance survivability. Operation Iraqi Freedom highlights this trend. During the first phase, US and coalition armies used weapon systems designed for high intensity warfare, offering mobility over any terrain with high level of protection and strong firepower. Yet, the same units were also assigned for the follow-on security and sustainment phase, which, initially required only civic, logistical supply and support activities using unarmored vehicles (like HMMWVs and trucks).

Unprotected vehicles rapidly became easy prey to irregular insurgent ambush attacks first from firearms and later, improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Every success boosted the insurgent’s moral, encouraging them to be more sophisticated and daring, while the coalition troops turned defensive, applying makeshift armor to the unprotected vehicles. At the beginning, the Coalition deliberately tried to avoid throwing in their heavy armor, in an attempt to de-escalate the situation and maintain ‘low signature’ presence in the city streets. However, suffering mounting casualties, the rag-tag makeshift armor had to be replaced by more standardized up-armoring kits installed in-theater by the support teams or back at the depots in Kuwait. The armor kits provided reasonable protection against small arms but, as proven by the mounting casualties, were totally inadequate against the growing IED threat.

During this period the Army increased the procurement of ad-on armor for HMMWVs, and purchased thousands of new armored HMMWVs, installed protected cabins for trucks, and bought over a hundreds of new Armored Security Vehicles (ASV), for convoy escort security and routine patrols. Other efforts were made to protect troops during transit and transport, as well as at checkpoints and guard posts. Armor improvements were provided to Bradley tracked armored vehicles applying reactive armor kits and counter IED appliqués, while slat armor was installed on the Strykers to augment their protection against deadly RPGs. Even the heavily armored Abrams tanks received new armor upgrades, as part of the Tank Urban Survival Kit (TUSK), enhancing their protection beyond the frontal arc, into an all-round armor suit meeting various threats encountered in typical urban area combat.

Additional parts of “Vehicle Armoring – MRAP and Beyond” article: