Today military forces use Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) in many roles, primarily for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) supporting all echelons, from the strategic to the tactical level. Drones are also used for strike missions, particularly against time-sensitive targets (TST), where these persistent platforms, that carry the surveillance and communications equipment, also operate the strike weapons, providing the only means possible to deliver an attack in the shortest time possible. These capabilities enable combat forces or agencies engaged in clandestine operations to quickly strike high-value targets before they move out of range or out of sight.

Challenges to Drone Operations

Today, drone missions are typically conducted in low-intensity warfare, against insurgents in conflict zones or over lightly defended territory where the drones, relying on modern Position, Navigation and Timing (PNT) derived from Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), advanced communications and satellite links to enable remote control.

Large drones are also susceptible to anti-aircraft fire. Therefore, successful operations over hostile areas require operators to gain the freedom of action – maintain aerial and spectrum superiority and access to operating bases in neighboring countries.

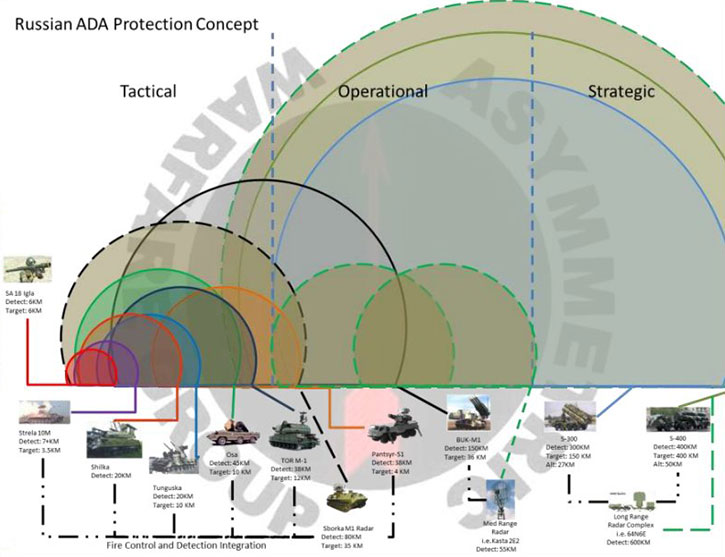

Until recently such operations have primarily taken place in uncontested airspace, where the adversary did not have the means to threaten UAS above a minimum altitude. This situation is changing rapidly, with the proliferation of electronic warfare capabilities compromising drone’s navigation positioning and communications capabilities, as well as man-portable air defense missiles (MANPADS) and air defense artillery that can target larger drones at low to medium altitudes. These threats become even higher when drones are called on missions in high-intensity warfare. To enable efficient operation in current and future conflicts drone capabilities must transform to cope with anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) battlespace.

A near-term solution is equipping medium and large drones with autonomous countermeasure systems, comprising of jammers, electronic warfare systems, and countermeasures, such as flares and directional lasers. Such systems have been deployed in recent years by several manufacturers, such as the Light Spear pod from Elbit Systems’Elisra. Light Spear forms an autonomous and complete electronic attack and self-protection system that loads on the drone’s underwing pylon. Equipped with the system, a drone improves the ability to collect accurate intelligence in highly hostile environments and improve its survivability against advanced threats.

Based on multiple Digital Radio Frequency Memory (DRFM) jamming channels working in parallel, the system can cover a wide spectrum range. The low Size, Weight, and Power (SWaP) consumption make it well suited for UAS platforms operating in hostile environments.

Drones and the Third Offset Strategy

Such transformation is likely to result in broader and more profound adoption of unmanned systems, far beyond today’s remote supervision, automated guidance and control functions. New capabilities that will aid, supplement and replace manned operations in roles considered too dangerous for humans to take. Integration of large masses of unmanned systems will also introduce concepts of operations (CONOPS) unimagined before, that will challenge and offset current or future military capabilities.

Such drones will be able to function without human interaction or supervision for the majority of their mission, thus remain silent throughout their missions. Many drones will be able to operate simultaneously as swarms – groups of tens, even hundreds of individual platforms, synched to act as a group, each and everyone pursuing different aspects of the common missions. Using such CONOPS drone swarms would be able to take out the enemy’s critical and most vulnerable nodes, such as early warning radars, advanced surface-to-air missiles, or command and control elements, overwhelming such targets by expendable mini-drones.

More in the ‘Future Autonomous Drones‘ review:

- Step I: Minimizing Dependence on Human Skills

- Step II: Mission Systems’ Automation

- Step III: Higher Autonomy Becoming Affordable

- Step IV: Teams, Squadrons, and Swarms of Bots

More in the ‘Future Drones’ series: