Part 3 of 3 in a special series about the role of Kurds in the war with ISIS

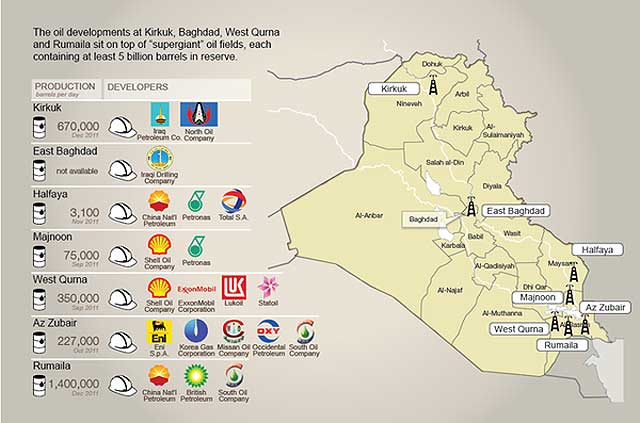

With the situation in Iraq and Syria changed, energy became key to the carefully improving relationship between Ankara and the semi-autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan. Turkey needs the oil produced there, pumping around 120,000 barrels a day through a 600-mile long pipeline from Kirkuk to the southern Turkish port of Ceyhan.

Historically, Turkish governments regarded Iraqi Kurds with deep suspicion, often intervening militarily to stop what they viewed as support for the bloody Kurdish insurgency inside Turkey. However, the latest boom in the Kurdish economy — and the subsequent success of Turkish companies there — has transformed relations between the two former enemies to thriving coexistence. Today, according to Turkish officials, there are already some 1,200 Turkish companies operating in Kurdistan, bringing in as many as a hundred thousand Turkish workers.

For the Kurds, the key to independence lies in exploiting and exporting their oil reserves, a trend that is just beginning. Since 2003, Kurdish leaders have opened their oil fields to Western companies, to explore, drill, and produce. It turns out that the Kurds are sitting on as many as 55 billion barrels of oil — a quarter of Iraq’s total reserves. 29 companies, among them Exxon Mobil and Chevron, are working in Kurdistan; the region currently maintains a relatively modest production of about two hundred thousand barrels a day. If the Kurds are able to sell their own oil, it will have to flow through Turkey, their only neighbor with a pipeline leading into the Kurdish region.

Under the growing threat of ISIS, the Kurds appear, for the first time, remarkably united in their eagerness for an independent state. Still, beneath the surface is a deep current of frustration with Masoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani, the leader of the other major party, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (P.U.K.). The historic quarrel between the Kursdish ruling families is well known and has derailed efforts for unification in the past, presenting a major roadblock for their independence.

While oil could become a crucial driver for an eventual unification, water would provide the lifeline of such state. Water is a prime strategic element in the dry Middle East and strangely, the Kurds are sitting directly over the most important water resources in the eastern Mediterranean region. Euphrates and Tigris – the two famous rivers of the Ancient Mesopotamia have seen the rise of ancient civilizations. The control of regional water resources has been a continual source of tension between modern Turkey, Iraq and Syria, and may likely pose even greater problems in the near future.

The Rivers Tigris and Euphrates flow downstream from Turkey into Syria and Iraq, where they provide the principal water source for individual and community livelihoods. Given the importance of these resources, there has been a history of disputes over the construction of dams and other water regulation projects along the rivers. These regional interstate hydro-political dynamics are bound to affect the Kurdish population extensively, as the Iraqi Kurdistan plays a pivotal role in controlling the majority of the Tigris river flow into Iraq. Moreover, the geo-politics of water in the Euphrates-Tigris basin are bound to remain highly contentious due to their direct link to issues of the Kurdish national independence and sovereignty. The Tigris-Euphrates basin, populated largely by the Kurds in all three riparian countries of Turkey, Syria and Iraq, has often been cited as the second most hydro-politically important region in the Middle East. The recognition of its significance for security of the region remains divided along the previously indicated lines of argument.

In the meantime, however more urgent matters seem to determine the regional political scene and that is the creation of the new Islamic State by ISIS. Following their dramatic success taking Mosul and, having full control of Anbar and parts of Syria, ISIS’ fighters turned south, toward the city of Kirkuk. Situated only 160 miles north of Baghdad, Kirkuk has been an object of dispute between the Arab-dominated governments in Baghdad and the Kurdish population. Over the years, Kirkuk had been subjected to campaigns of ethnic cleansing, its Kurdish majority reduced by waves of expulsions and government encouraged Arab migration from the south. To many Kurds, Kirkuk is sacred ground, a vital component of an independent state. Kirkuk and the rest of the contested region contained as many as a million Kurds, as well as oil reserves thought to amount to at least ten billion barrels.

Meanwhile, the still very hesitant Turkish support will probably continue as long as the aspirations to nation-building are strictly confined to Iraqi Kurdistan but this could change, as Barzani’s forces gain substantially in the war with ISIS. So far, the regional Kurdish government in the capital Irbil is playing its cards skilfully. It is all a matter of balancing those long-term political dreams against the practical diplomatic realities of the moment. For now, it feels as though Iraqi Kurdistan believes it can work on building a new nation-state as long as it keeps its real political aspirations carefully under the radar.

Strange as it may sound to western ears, from Turkey’s new perspective, these days, Kurdish autonomy does not look so half bad, as it was before the ISIS crisis. The portions of northern Iraq and Syria that are under Kurdish control are stable and peaceful — a perfect bulwark against threats, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) on Turkey itself. And that is why Turkey has been on relative good relations with the Iraqi Kurds, and could expand into other Kurdish territories, if the war with ISIS develops favorably for Ankara’s regional aspirations.

ISIS’ advances in Iraq — including a June 11 attack on the Turkish consulate in Mosul, during which the group took Turkish diplomats and security officials hostage — has added urgency to the drive to improve relations between Turkey and Iraqi Kurds. It now seems safe to say that if the Iraqi Kurdish regional government declared independence Ankara could perhaps become the first capital to recognize it. In today’s Middle East, in other words, ISIS is a bigger threat to the Turks than a Kurdish independence in Iraq.

Whereas Turkey’s ties with the Iraqi Kurds have improved in recent years, Ankara’s relations with the Syrian Kurds have remained rather bitter. This is because, unlike in the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) where Iraqi Kurdish groups hold more sway than the Turkish Workers Party (PKK), which has been for decades Turkey’s mortal enemy,

the latter is very popular among the Syrian Kurds. With the emergence of ISIS, the Syrian Kurds’ calculations might be changing. The Democratic Union Party (PYD) and PKK have strong secular tendencies and oppose ISIS and its austere version of Islam. The PYD now controls three Kurdish exclaves in northern Syria, all of which are flanked by Turkey to the north and ISIS to the south. And unlike the Assad regime, ISIS has shown no inclination to trade favors with the Kurds. The Syrian Kurds’ future could now be in Turkey’s hands, and if matters will heat up, full Turkish military and security cooperation could be forthcoming.

Turkey cannot grow closer to Iraqi and Syrian Kurds without making peace with its own Kurds, which virtually dominate eastern Turkey and much of its strategic assets there. After decades of battle, the PKK could still easily derail any rapprochement between Turkey and other Kurdish groups, especially the Syrian Kurds, by telling the PYD to reject Turkish offers. What is more, the PKK could launch attacks in Turkey if it feels that it is being left out of a potential deal between Ankara and the Iraqi Kurds.

When ‘push comes to shove’ in this region eventually, Ankara’s only allies in the Middle East might just be the Kurds. Likewise, the Kurds’ main ally could soon be Ankara. Working together, they will try to halt or even defeat their common enemy – ISIS – from becoming a regional power. Turkey’s government is treading a delicate line – attempting to calm its core nationalist voters at home, while bowing to pressure from Washington to help the Kurds in Syria battle Islamic State. Under such stringent conditions, a Turkish controlled Kurdish autonomy seems not to look as half bad to the Ankara leaders.