Sgt. Shaina B. Schmigel, the paratrooper who died Friday May 30 during an airborne training exercise at Ft. Brag was using the new T-11, the Fayetteville Observer reports. Schmigel was a member the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division. The cause of Schmigel’s death is under investigation, and officials have not said if the parachute played a role.

While Army records of Fort Bragg parachute operations have determined the T-11 to be a safer Parachute that is less likely to injure parachutists, this system has been associated with at least two fatal falls since its introduction on Fort Bragg in 2009. One other death took place with a third, less common type of Parachute during that time span.

In 2011, the Army suspended the use of the T-11 after a training death on Fort Bragg. Sgt. Jamal Clay, a soldier with the 82nd Airborne’s 3rd Brigade Combat Team, fell to his death when his T-11 parachute malfunctioned in June of that year. A safety investigation board determined the T-11 failed because of debris within the parachute and improper packing. Clay did not activate his reserve parachute. The T-11 was reintroduced in March 2012, with Fort Bragg’s then-commander, Lt. Gen. Frank Helmick, being the first to use the parachute to show leaders’ confidence.

The Army has closely followed the safety records of the new parachutes that have determined the T-11 to be safer to parachutists

Since 2012 the Army is increasing its production of the T-11 parachutes, with 14,000 systems already in place at Fort Bragg, phasing out the T-10 parachutes.

The Army has closely followed the safety records of the new parachutes that have determined the T-11 to be safer to parachutists. Compared with the T-10D, injuries were 43 percent less likely to occur with the T-11, according to a study by the U.S. Army Public Health Command. The latest study released in February 2014 has analyzed data from more than 130,000 jumps, most of them performed at Fort Bragg’s drop zones.

The study looked at 1,101 injuries and found that soldiers were injured on average 8.4 times per 1,000 jumps. Most of those injuries – about 88 percent – were associated with ground impact, but were less common with the newer parachutes.

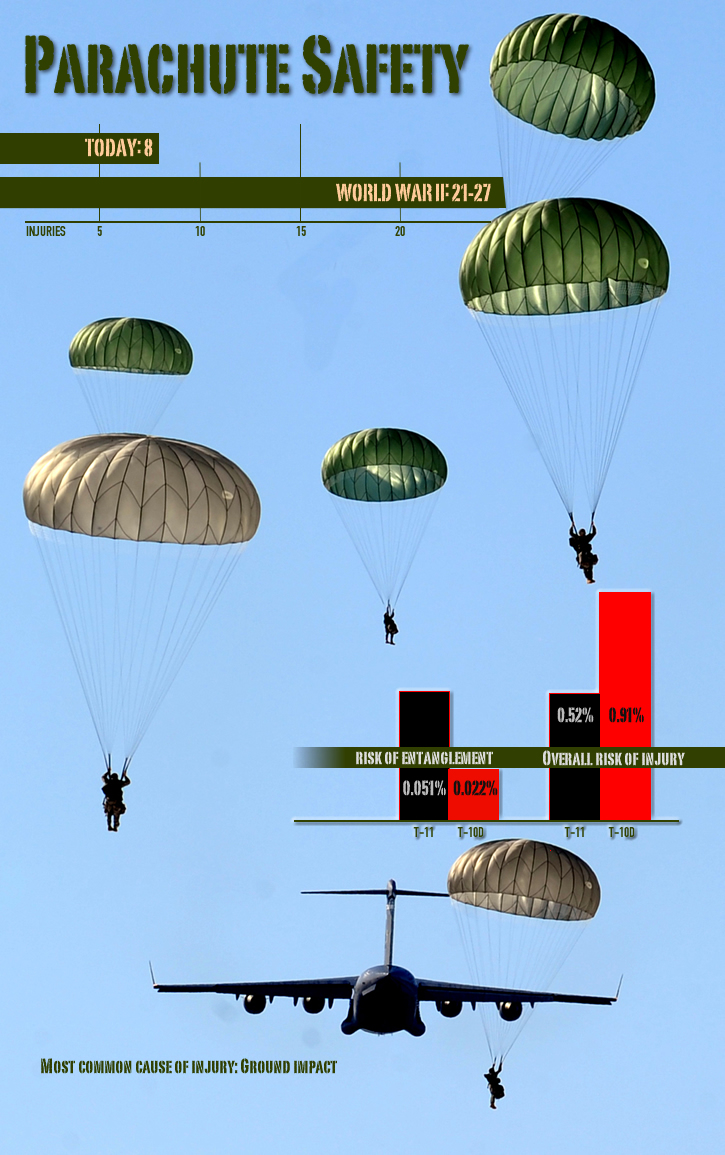

Paratroopers using the T-10D were injured 9.1 times per 1,000 jumps, according to the study. Injuries occurred 5.2 times per 1,000 jumps in the T-11. Other factors that made jumps more dangerous include jumping at night, carrying a full combat load or jumping in higher winds or higher temperatures.

Controlling for those factors, the Army study found the T-11 still was safer for every category except entanglements.

The risks of entanglement and injury from entanglement were higher with the T-11, according to officials, but the incidents were rare, regardless of the parachute. Entanglements occurred in .51 per 1,000 jumps in the T-11 and .22 per 1,000 jumps in the T-10D.

Armywide, parachuting injuries are the sixth leading cause of hospitalizations among active-duty soldiers, officials said. But injury rates have improved over the decades. During World War II, there were 21 to 27 injuries per 1,000 jumps, according to officials. The 82nd Airborne’s historical injury rate is 11 per 1,000 jumps.

The T-11 was developed over several years in response to a need for Army parachutes to carry heavier loads

The most common injuries on Fort Bragg over the 31/2 year study were concussions, ankle sprains and lower back sprains, with concussions making up more than a third of all injuries. Fractured or broken bones accounted for about 13 percent of all injuries.

The major differences between the T-10 and the T-11 are that the T-11 allows more weight to be carried by the paratrooper and is able to handle a load capacity of more than 400 pounds to accommodate today’s paratrooper and their equipment load. The new parachute is cruciform in shape, as opposed to a circle, like its predecessor, with a larger surface area and diameter. The T-11’s design aids in slowing the rate of descent from 22 feet per second to 19 feet, which significantly lowers the possibility of jump-related injuries. The cruciform shape of the T-11 parachute helps to vertically stablilize the parachute soon after deployment, eliminating the oscillation experienced with T-10. Researchers considered these oscillations likely to increase injury risk by increasing the impact energy on ground contact.

The T-11 was developed over several years in response to a need for Army parachutes to carry heavier loads. The T-10D held a maximum weight of 350 pounds (159 kg) and was developed during a time when the average load of a soldier and his equipment was 300 pounds (136 kg), according to officials.

By 1989, when paratroopers jumped into Panama as part of Operation Just Cause, 4 percent of all paratroopers carried more than 350 pounds (159 kg). More than a decade later, during combat jumps into Iraq and Afghanistan, paratrooper loads averaged between 327 and 380 pounds (148-172 kg). The T-11, which began replacing the T-10D in 2010, can hold 400-pound (181) loads.