The existing bomber force cannot cope with new challenges indefinitely. As countries like China pursue anti-access strategies and more agile air defenses become available to potential adversaries, the U.S. must recapitalize its aging bomber fleet. Failure to do so could eventually result in major military setbacks, since future enemies will doubtless attack the joint force where it is weakest. Defense analyst Lauren B. Thompson comments in a recent report published by the Lexington Group. .

Bombers have played a vital role in recent conflicts. From the Balkans to Afghanistan to Iraq to Libya, the Air Force’s fleet of long range, heavy bombers has proven highly useful in defeating diverse adversaries. Bombers typically deliver a disproportionate share of the munitions expended in air campaigns, and the advent of precision-guided weapons has enabled them to hit many targets in a single flight — day or night, in good weather or bad.

Heavy bombers are uniquely versatile and cost-effective. The defining features of heavy bombers are long reach and large payloads. These features have allowed them to adapt to changing threat conditions in a way that smaller tactical aircraft — manned or unmanned — could not. For instance, the B-52 bomber debuted as a high-flying nuclear bomber, but later became a low-level penetrator, then a conventional bomber, and today a mixed-use strike aircraft that can launch cruise missiles.

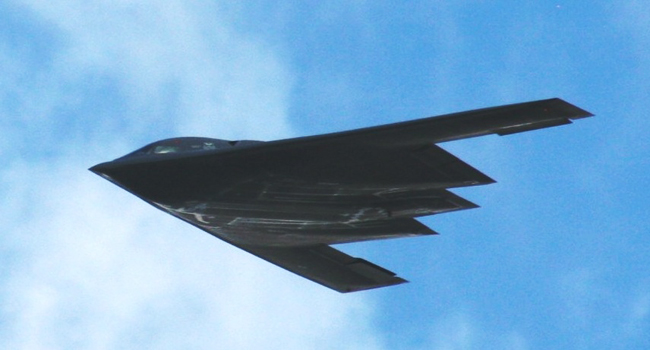

The newest planes in the U.S. heavy bomber fleet were designed over 30 years ago. The current bomber force is capable but aging. The heavy bomber force includes 76 B-52 Stratofortresses averaging 50 years of age, 63 B-1 Lancers averaging 28 years, and 20 B-2 Spirits averaging 20 years. Each of the bombers can deliver a mixed payload of precision munitions to an unrefueled range of 6,000 miles or greater. The B-52 is the only standoff cruise missile carrier in the fleet, the B-1 is the only supersonic bomber, and the B-2 is the only stealthy bomber. All three are facing age-related issues.

The world has changed in fundamental ways since they were first conceived. The Soviet Union has fallen and China has risen. The information revolution has transformed commerce and culture. Old technologies of mass destruction have spread to new nations, and new technologies have empowered extremists of every stripe. In sum, virtually every feature of the threat environment has changed since America last commenced development of a new bomber. At some point, it will no longer be feasible to deter and/or defeat emerging threats with combat systems designed for another time.

Although America has encountered unexpected threats in this new age, it continues to enjoy global air dominance. Non-traditional enemies such as the Taliban have lacked the means to challenge U.S. forces in the air, or at sea, or in conventional combat on land, and so have resorted to asymmetric strategies. The legacy bomber fleet and tactical aircraft in the joint inventory have proven highly adaptable to the demands imposed by new kinds of warfare, mainly because there was so little that irregular adversaries could do to deny access to their airspace. As a result, military planners have been under greater pressure to upgrade ground combat systems than their counterparts in the air.

As the long-range bomber force ages, it will gradually come to present an opportunity for rising powers or movements that think they can carve out sanctuaries by denying U.S. air power access to those areas. If they can force U.S. aircraft carriers to remain far away and hold at risk the nearby land bases used by U.S. military aircraft, then the bomber force becomes the sole impediment to their plans short of America launching ballistic missiles. Ballistic missiles will seldom be a cost-effective, proportionate or even credible response to the threats America faces.

Thus, developing a Long Range Strike Bomber that can gradually take over the most demanding missions of America’s fading Cold War bomber force is an indispensable step in preserving the nation’s security through mid-century. A new bomber will strengthen nuclear deterrence by allowing U.S. leaders to hold at risk the most valued assets of aggressor nations with a strike system that can be quickly recalled or retargeted as conditions dictate. A new bomber will enable the joint force to deliver tailored effects against a wide array of conventional threats at distances beyond the reach of tactical air power, in circumstances where reliance on standoff munitions would be either unaffordable or simply unexecutable.

Most importantly, though, a new bomber would be a hedge against the uncertainty military planners face during a period of unprecedented change in human civilization. Having failed to anticipate most of the major threat developments over the last hundred years, it would be foolish indeed for U.S. leaders to think they have a better grasp of the future now that every facet of human experience is subject to simultaneous change. What they can know, though, is that being able to reach anywhere on earth with survivable, versatile air power will continue to be a crucial feature of U.S. military capability. Failure to preserve that capability by developing the Long Range Strike Bomber could have fatal consequences for U.S. warfighters, and many other Americans.

Efforts to buy a new bomber have been repeatedly delayed. When the Cold War ended, the defense department terminated production of the B-2 and ceased development of new bombers for the first time since the 1920s. Plans to pursue a next-generation bomber were delayed by changing threat conditions and the appearance of new technologies that could bolster the performance of aging planes. As a result, the U.S. has not developed a new heavy bomber in three decades.

The Air Force has plans to develop a new bomber. The Air Force has budgeted $6 billion for development of a Long Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B) between 2013 and 2017. The service says it will buy 80-100 aircraft at an average cost of $550 million each, with initial operational capability in 2025. Although details are secret, experts predict the new bomber will be able to operate autonomously in hostile airspace, carrying a mixed payload of precision munitions over intercontinental distances.

Existing strike capabilities must be upgraded as a new bomber is developed. It will take 20 years to develop, produce and deploy LRS-B. During that time, the Air Force must continue sustaining legacy strike aircraft to deter aggression and defeat aggressors. Each of the bombers in the current fleet requires upgrades to enhance connectivity with other friendly forces, expand the range of munitions that can be delivered, and cope with age-related maladies such as metal corrosion.

Failure to develop a new bomber could have fatal consequences.