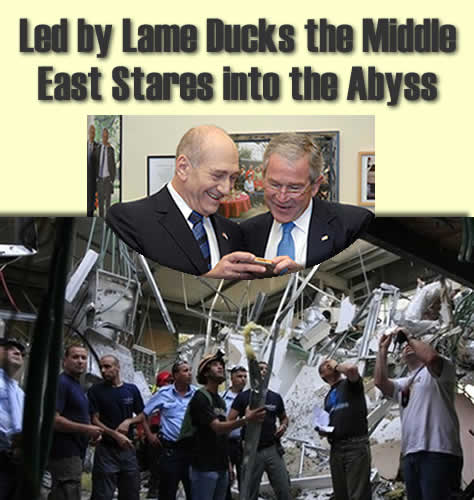

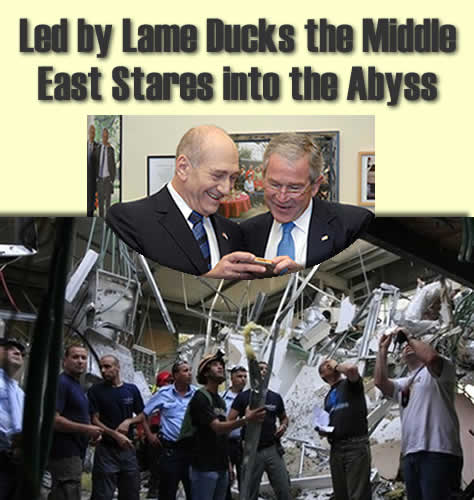

Nothing can perhaps illustrate the bizarre situation, that exists in the Middle East in Spring 2008, than two events, which occurred almost simultaneously, seemingly on two different planets, but a mere seventy kilometers from each other, on Wednesday evening. In Jerusalem, under a relaxed atmosphere of feted tranquility, among dignitaries celebrating Israel’s 60th birthday, two emotionally engulfed “lame ducks”, US President George W Bush and Israel Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, showered each other with almost painfully embarrassing superlatives. At precisely the same time, in Ashkelon, on the Mediterranean sea side- an Iranian rocket, fired by Hamas from Gaza, slammed into a human packed infirmary, seriously wounding scores of innocent women and children. The grotesque scenes, depicted live on TV screens clearly demonstrated the virtual dance macabre, under which the leaderless people of the Middle East are living these days: lot’s of irresponsible palaver, eye wash and illusion, but little hope.

As if to accentuate the utter bankruptcy of President Bush’s virtually impotent foreign policy in the Middle East, the current fiasco in Beirut has added another “lame duck” leader to his ludicrous team of losers.

The Hezbollah “Blitz” on the Sunni quarters in Beirut, last week, has not only caused severe shockwaves inside Lebanon, but clearly demonstrated Washington’s dangerous lack of determination to meet such contingencies with an immediate show of force. In fact, not only the Bush Administration, but the entire Sunni world remained passive, apart from irrelevant rhetoric, which has convinced the Ayatollah’s in Tehran and Bashar Assad in Damascus, not to mention their vassal, Hassan Nasrallah that they could get away with anything they wished, in humiliating their hapless pro-Western adversaries. While Beirut burned- all that the West and the Sunni Arab leaders could offer was shedding some consolatory ‘crocodile tears’ to the embattled Prime Minister Fouad Seniora.

Recent events in Gaza, the West Bank, Baghdad and now, Lebanon, could serve as a prefect example to what extent the Bush administration “Pax Americana” has already deteriorated the turbulent Middle East-onto the brink of total political chaos.

In fact, by failing in every way, the Bush administration has proven itself abysmal in executing it’s own coherent Middle East policy- which has already proved disastrous to the entire region.

The stark reality is, that President George W Bush, after two botched terms in office, is leaving behind a lot of scorched earth here. The situation in Iraq is dangerously gridlocked; Iran is still actively pursuing its nuclear program; al-Qaeda continues to threaten all Western values. The illusory two-state solution for Israel and Palestine is still far from being implemented, if it ever will be. His push for democratic elections in the territories has produced Hamastan in Gaza, a dangerous destabilization of a Lebanese political balance in favor of Iranian-backed Hezbollah and even the dramatic rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in Mubarak’s Egypt.

Washington’s irresolute actions in the strategic Gulf Region, have already brought about a dangerous shift towards a more and more dominating Shi’ite hegemony bid, for renewed religious loyalty among the Gulf States Shi’ite population minorities.

If the new incoming US administration will fail to rally the ‘moderate’ Sunni leadership in time, the Tehran Ayathollah’s under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad will no doubt exert a massive onslaught on the Sunni Gulf region, extending their long-aimed strategy of the so-called “Shi’ite Crescent” from Iran, to the Gulf States brim, over southern Iraq, through Syria-to a Hezbollah-ruled, Lebanon and if not stopped by a determined Israeli countermove, the Iranian-backed Gaza Strip forward base on Egypt’s doorstep.

The root of all this evil lies at the epic failure of Bush’s democratization agenda as a regional strategy.

The Bush Administration allowed the participation of the terrorist groups such as Hamas and Hezbollah in democratic elections in the Palestinian Authority and Lebanon without insisting that they give up their arms, recognize Israel’s right to exist or renounce the killing of innocent civilians. Both Hamas and Hezbollah have already become major players in the Mid East power struggle, serving the strategic aims of Tehran and all this, thanks to George W Bush and Condoleezza Rice’s shortsighted policy and total ignorance of the traditional local affairs, in this highly turbulent and explosive region.

Perhaps the latest and most dramatic development, is currently happening in Lebanon, where the Iranian backed Hezbollah-led Shi’ite opposition is on the way to obtain dominant political power, in determining the sensitive balance, which has maintained Lebanon, for decades, as a semi-democratic Arab state with a pro-western orientation.

But there is much more to this drama, which may, for the time being subside into another short-termed lull, before the real storm breaks, when Tehran gives the order. Hezbollah has shown, what it can do, just as Hamas did last June, in its Gaza lightning take-over.

Hezbollah’s brilliant demonstration in taking over western and central Beirut, within hours, has had the effect of adding another link to the pro-Iranian chain already encircling Israel. In many ways it may become a more damaging setback for Israel’s national security than the Palestinian Hamas’ seizure of the Gaza Strip. If not stopped in time, by determined action backed by the US, Israel will be confronted, in foreseeable future, by multi-front and multi-dimensional threats, ranging from Iranian ballistic missiles, with or without non-conventional warheads, medium-range rockets from Lebanon and Syria, with or without chemical weapons grade capabilities and short-range rockets from the Gaza Strip, or even from the West Bank.

This presents a challenge to Israel’s national security, second to none in the world and only a highly convincible deterrent, led by a determined leadership can prevent this from happening. Unfortunately, the current political situation in Israel is highly dubious. Israel’s prime minister, defense minister and foreign minister are all too busy with the political fallout of the bribery case against Ehud Olmert to lift a finger to arrest Lebanon’s decline to a Tehran satellite before it is too late – any more than Hamas was stopped from developing into a major military menace. Once the celebrations in Jerusalem will subside and Israel returns to reality, it will be time for its leadership to wake up, and gird to face the challenges- before it will be too late.

At

At