“Vehicle Armoring – MRAP and Beyond“ < Page 8 of 8 >

The need for better protection for troops facing threat in the combat zone is obvious. They must be equipped with the best means available providing them the best protection suitable for their mission. However, protection is not the goal but one of the means to achieve the mission. It should assist, not hinder mission success.

Up-armoring of existing vehicles is an ongoing process that must continue to meet prevailing threat levels regardless of the availability of other vehicles. In asymmetric warfare, all vehicles engaged in combat operations (not only the combat vehicles) should be protected. Since the threat is evolving, their protection should be upgraded continuously. This process is evident when studying the changes made to combat vehicles in Iraq since Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003 and it is continuing today as well.

An up-armoring project is usually part of a more comprehensive upgrade program, where the vehicle’s automotive system undergo adaptation to carry the extra loads, better handling weight distribution which may not have been the same as originally designed, particularly when the vehicle carry the new armor and full mission load.

In the past, US forces considered armor protection only necessary for combat fighting vehicles, including armore personnel carriers, leaving most of the rest combat service and support elements virtually unprotected. Unlike current vehicles, armor upgradability was not designed into these vehicles at all. When necessary, light armor was fielded with specific vehicles (such as the armored security vehicle, used by military police for road security missions).

This albeit shortsighted approach determined the requirements for curbs weight, (CVW) payload and gross vehicle weigh (GVW) of tactical and support vehicles, such as the HMMWV, FMTV HEMTT and other vehicles. The HMMWV was an exception, as it was also designed as a weapon carrier (missile carriers, reconnaissance vehicles) for specific combat roles and therefore, had provisions to receive add-on armor despite its inherent, limited load capacity. Yet, restricted by weight and design limitations, the armor used with HMMWVs provides good protection against some threats but leaves much to be desired against others.

The growing demand for armor protection emerged as coalition forces realized the increasing threat encountered during the new asymmetric conflicts erupting in Southwest Asia and the Middle East. All combat vehicles, armored and unarmored, had to go through upgrades process to encounter the new threats. Modifications included some unorthodox means, such as spray-on ballistic armor, which was thought to offer an ‘instant’ protection from small-arms, application of sandbags for side and top protection and slat cages, widely deployed with almost all light combat vehicles in theater. Another concept offering rapid installation and replacement of armor tiles is the LAST armor, utilizing innovative hook-and-loop (Velcro like) attachments fasteners to keep the tiles in place. Most up-armoring upgrades are made of kits of armor tiles externally added to the vehicle’s body parts, using welded bolt mounts. This method enables rapid repair in the field by the replacement of combat damaged armor tiles. Similar applications are used for slat armor, which offer ‘statistical’ protection from shaped-charge threats, significantly enhancing the vehicle’s survivability to RPG attacks.

Various concepts of armoring are used to minimize the down-time vehicles undergo in the process of armor installation. Trucks are particularly quick to receive added protection, replacing the original cabins with armored cabs. Much more work has to be done on light vehicles, such as the HMMWV, to fit armor on a structure that was never designed to carry these extra loads. In fact, the up-armor kit consists of considerable ‘dead weight’, designed to carry the heavy doors, or keep all elements in place. The manufacturer of the HMMWV, AM General began to produce armored versions of the vehicle last year in an effort to expedite the delivery of protected vehicles to the combat troops.

The US military identified this weakness even before the current conflict, and outlined its Long Term Armor Strategy (LTAS) to define mandatory protection for all future wheeled tactical vehicles. These included new generations of scout cars, command vehicles, troop carriers, logistical and support vehicles. LTAS defines vehicle protection in two levels – a ‘baseline’ protection designated ‘A-kit’ and ‘improved’ add-on system known as ‘B-kit’. The baseline protection will protect from firearms, as well as mines and blasts. All military vehicles will be produced with this capability, enabling efficient air mobility, minimizing vehicle wear and improving life cycle cost. To operate in contingencies where more substantial threats exist, vehicles will be provided with an appropriate ‘B kit’ as required to meet the specific threat. This method will enable the military to match the vehicle protection to specific threats and even rotate ‘B-Kits’, between units deployed to the theater of operation, without having to build new armored vehicles for each conflict.

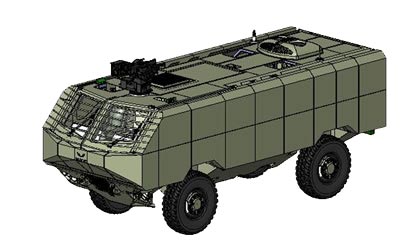

The first family of vehicles designed to LTAS standards from the start is the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV), a family of new combat and combat support vehicles designed for all contingencies, offering the use of threat-adaptive ‘B-kit’. All JLTVs will have V shaped hulls, protecting from explosions and mines, as well as basic bulletproof armor. Since the baseline armor is part of the vehicle, additional armor weight will facilitate net protection, since all the structural elements and attachments carrying the appliqués armor kit will already be provided in the baseline. LTAS concepts have partially been applied to existing vehicles upgrades, including the FMTV family of medium trucks (FMTV), and Heavy Expeditionary Transporter (HEMTT/HET), M939, M915 and HET and, to some extent, to the HMMWV. Yet, the current designs and limited payload capacity are limiting the full utilization of the new strategy.

This strategy is also implemented into the Pentagon’s MRAP acquisition program. Responding to the urgent need of heavy armor in Iraq, the initial 6,000+ vehicles produced under the current MRAP program do have the full protective suite expected to be fielded in the future model. The Marine Corps Systems Command already embarked on a follow-on MRAP program called MRAP II, offering better protection and mobility. This new program will open new opportunities for manufacturers that have not been qualified for the first MRAP program. Armor upgrades will also be applicable to all MRAP vehicles. Some of the armor upgrades of MRAP II are expected to be retrofitted to the early production batches MRAP vehicles.

Additional parts of “Vehicle Armoring – MRAP and Beyond” article:

Coyote, built by Advanced Ceramics Research is designed as an air deliverable, optional expendable UAV weighing up to 6.4 kg, (14 lbs). With folded wings, propeller and tail, it fits into a standard A-size sonobuoy container. After release from its container, Coyote can dive to lower altitude, using its vertical fins as control and stabilizing surfaces.

Coyote, built by Advanced Ceramics Research is designed as an air deliverable, optional expendable UAV weighing up to 6.4 kg, (14 lbs). With folded wings, propeller and tail, it fits into a standard A-size sonobuoy container. After release from its container, Coyote can dive to lower altitude, using its vertical fins as control and stabilizing surfaces.